Father, Here Is My Little, My All

Though we may mourn the immense gulf between what we hold in our hands and what we wish we could give to so great a Savior, in some ways this sense of our poverty is part of what we bring.

Now may be the time to consider taking some things off your plate. I’d actually been about to heap on some new ministry opportunities, and said as much before laughing weakly. A few days later, I wrote an email backing out of a new church initiative. I pressed Send and the tears welled.

I want to be led, but not this way. Give me burning conviction from the Scriptures, promptings of the Holy Spirit, and events too unlikely to be dismissed as coincidences. But to make choices informed by my body, by pain and weakness? Here I become a 2-year-old trying to shake loose a caregiver’s grip with all my squirming toddler might.

Motherhood especially has been a classroom in being led by way of constraints, but I suspect it’s also a natural part of getting older. As time passes, we become more aware of the limitations that, much like a river’s banks, have held and directed the flow of our lives. It turns out that I've always been constrained by my callings (as a mom, daughter, neighbor, friend, church member, citizen, etc.), my particular time and place, and my unique family history, ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, gifting, and body.

It’s the last bit that I’ve most often strained against, especially these days. When facing less-than-ideal circumstances, it has helped me to remember that just as trails are marked by the unyielding presence of the trees that line them, so God often makes my way known to me through interruptions. But with chronic illness, it’s not so much the redirection— God saying, “I want you to serve here, not there”— but the shrinking of my capacity that I am wary of. My body is dictating the vigor and pace I can walk this path, and it is painfully slow, halting even.

I think it may be helpful for you to hear this, my sister prefaced, shortly after my autoimmune diagnosis. She then told me about another woman, in ministry and chronically ill, who’d shared about needing to trust that there was no good thing God wanted her to do that she wouldn’t be able to do because she was sick.

I've been here before. God has been whittling away at this part of me for about as long as I’ve known him. Taking my raw yearning to be used by him for his glory and refining it in the heat of ministry, motherhood, now illness.

What if God won’t use me?, I’d said in high school, fearful that my sinfulness would render me out of service in the Kingdom. In God’s kindness, the mentor who heard my question didn’t assure me of all the great things I’d do for God. Instead, he’d gently pushed back with a question like, What if that’s not the most important thing. Years later, I was praying with thanks over a summer of what had felt like successful missions work, when the Holy Spirit blindsided me. I would’ve been just as loved by God, he reminded me, even if I hadn’t “done well.” I was undone.

Perhaps this is one reason Jesus rebuked the seventy-two returning to him with an excitement that had been similar to mine post-missions. Instead of joining in their celebration about the wonderful things they did in his name, he told them not to rejoice, at least not about that. Rather, they were to rejoice that their names were written in heaven (Lk. 10:20). I wonder if Jesus' redirection of their joy not only instructs us to prize God more than our work for him, but serves to reveal what he values most— that compared to all we accomplish for him, our hearts are his greater treasure.

I’ve been thinking about the widow’s offering lately in connection to Psalm 50, the way that, if God truly needs nothing from us, then he must be after something else in our sacrifices. And how, if he is not dependent upon our offering for his work, he is truly able to value gifts based solely on the hearts of the giver.

I've always been moved by the stories in the gospels of those who gave their little, but all, to Jesus. Stories of bread and fish broken, of two coins dropped in a box, of an alabaster jar emptied. It’s incredible to me that the God of the universe has seen to it that a record of these gifts would be written down for the ages. Yet it is precisely because he is so immense that he can delight in offerings so small. Because God isn’t bound by our resources, he can freely assess the value of our service in a completely different economy than human judgments of usefulness.

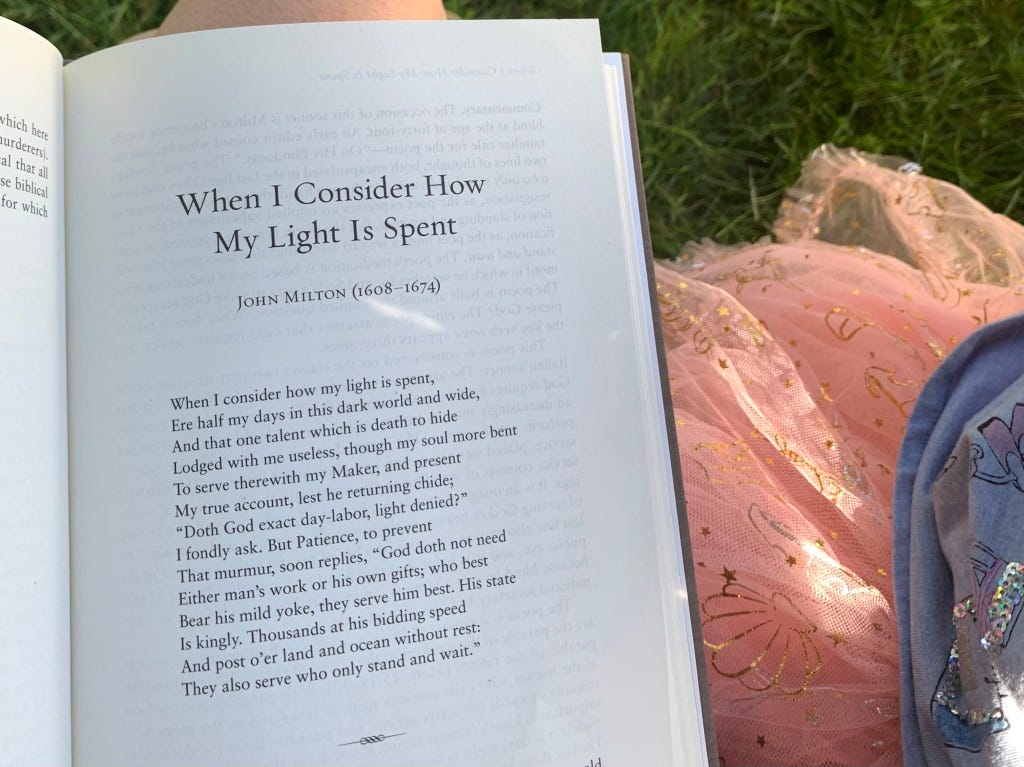

The poet John Milton touches upon this in his "Sonnet 19." Wrestling with a "soul bent" to serve his Maker, but limited in his capacity (most probably because he was going blind), he wrote: “God doth not need / Either man’s work or his own gifts; who best / Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best.” God is King, he writes, and has thousands doing his bidding. Therefore, Milton concludes, "those also serve who only stand and wait."

With so many needs around me and holding a shrinking plate, I am being forced to plead with God to work with what little I have to offer him. Yet even here, it’s tempting to put too much hope in what Jesus will accomplish with my loaves and fish. Surely, he loves to confound the strong by making his power known through the weak. He can and does multiply the efforts of those who serve him, establishing the work of our hands. But in the final measure, it isn’t even what God chooses to do with my meager offerings that determines their worth.

The large sums of the rich would no doubt end up being put to more use than two small copper coins. Mary’s perfume could have been sold and used for charity. Yet our Savior goes so far as to say that the first giver "put in more than all of them" because "she out of her poverty put in all she had to live on" (Mk. 12:41-44). The second, he defended publicly as doing a beautiful thing, saying, she had "done what she could" (Mk. 14:8). In both instances, Jesus recognizes the way these worshippers gave out of their limited supply and, in light of a gift earnestly given out of the confines of these limits, praises them.

The Apostle Paul writes similarly of the generous giving he sought from believers, saying, "For if the readiness is there, [the gift] is acceptable according to what a person has, not according to what he does not have" (2 Cor. 8:12). God knows both our hearts and the limits of our ability. So while he may ask for my all, he never demands more than that. I need to believe this, especially now.

A few weeks ago, my 5-year old walked ahead of me into Trader Joe’s. Greeted at the door by a display of flowers, he circled back toward me. Can I buy some for you? As soon as we unloaded the groceries at home, he brought the blooms over to me as if they were a surprise. This is for you! I'd bought the bouquet for myself but they were no less from my son.

To those who want to serve God with all your being, who have given of yourselves with a burning passion for his glory and yet find your Shepherd has led you down unexpected pathways— he is, and has always been, after our hearts. So it is that the feeblest heartfelt offering given by the lowliest of saints is not only seen, but received with gladness by our King.

Though we may mourn the immense gulf between what we hold in our hands and what we wish we could give to so great a Savior, in some ways this sense of our poverty is part of what we bring. We know we have little, but still we bring our all. Father, this is for you.